dFDA: A Decentralized Framework for Drug Assessment Using Two-Stage Real-World Evidence Validation

pharmacovigilance, real-world evidence, N-of-1 trials, causal inference, Bradford Hill criteria, treatment effects, adverse events, outcome labels, variable relationships, predictor-outcome analysis

1 Abstract

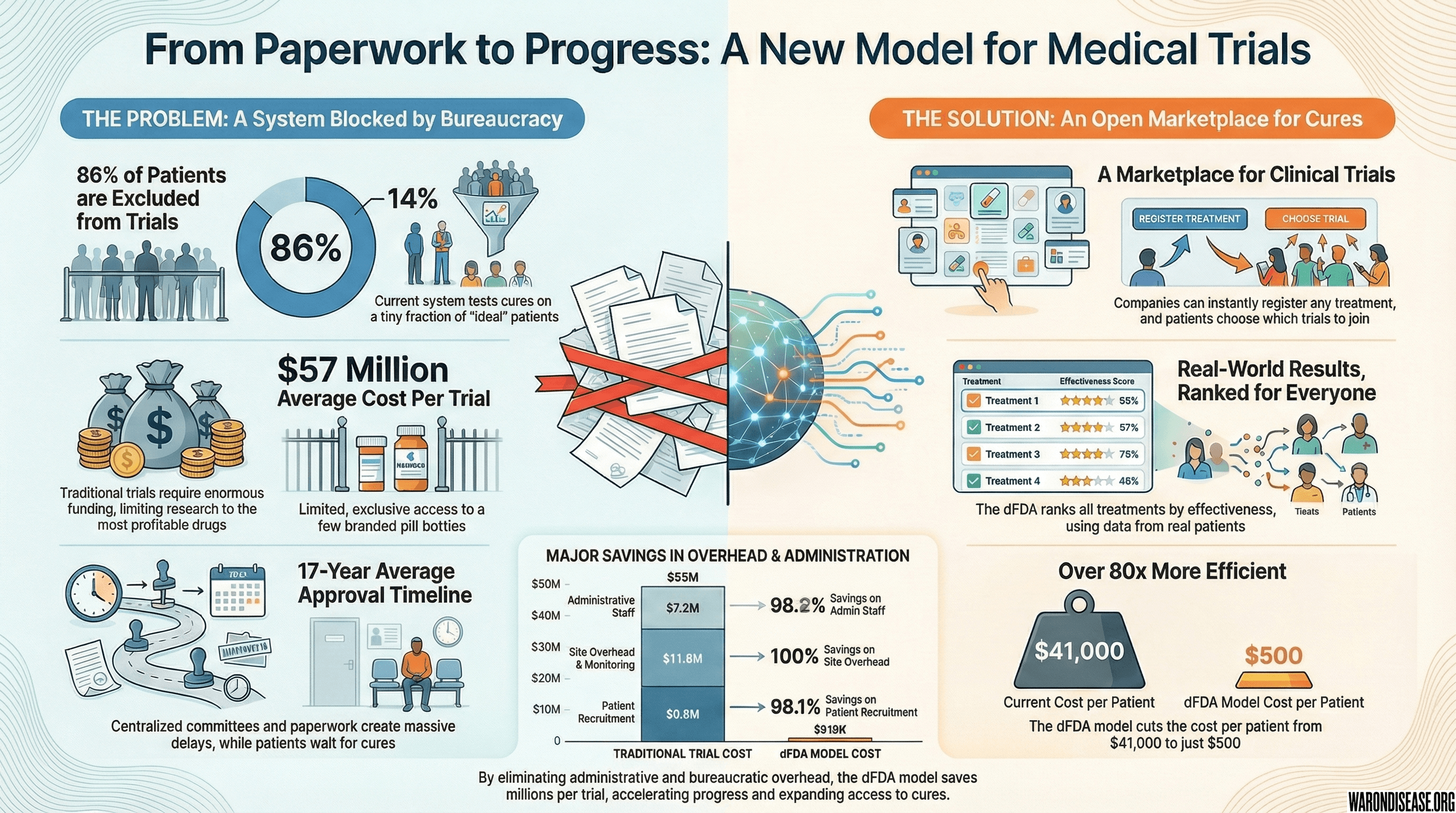

Current pharmacovigilance systems rely primarily on spontaneous adverse event reporting, which suffers from significant underreporting, lack of denominator data, and inability to quantify effect sizes. Meanwhile, the proliferation of wearable devices, health apps, and patient-reported outcomes has generated unprecedented volumes of longitudinal real-world data (RWD) that remain largely untapped for safety and efficacy signal detection.

We present a comprehensive two-stage framework for generating validated outcome labels with quantitative effect sizes:

Stage 1 (Signal Detection): Aggregated N-of-1 observational analysis8,9 integrates data from millions of individual longitudinal natural experiments. The methodology applies temporal precedence analysis with automated hyperparameter optimization, addresses six of nine Bradford Hill causality criteria through a composite Predictor Impact Score (PIS), and produces ranked treatment-outcome hypotheses at ~$0.100 (95% CI: $0.030-$1.00) per patient.

Stage 2 (Causal Confirmation): High-priority signals (top 0.1-1% by PIS) proceed to pragmatic randomized trials following the RECOVERY/ADAPTABLE model10,11. Simple randomization embedded in routine care confirms causation at ~$500 (95% CI: $400-$2.50K) per patient (82x (95% CI: 50x-94.1x) cheaper than traditional Phase III trials) while eliminating confounding concerns inherent in observational data.

The complete methodology includes: (1) data collection from heterogeneous sources; (2) temporal alignment with onset delay optimization; (3) within-subject baseline/follow-up comparison; (4) Predictor Impact Score calculation operationalizing Bradford Hill criteria; (5) Trial Priority Score for signal-to-trial prioritization; (6) pragmatic trial protocols for causal confirmation; and (7) validated outcome label generation with evidence grades.

This two-stage design addresses the fundamental limitations of purely observational pharmacovigilance (confounding, self-selection, and inability to prove causation) while maintaining the scale and cost advantages of real-world data. The result is a complete pipeline from passive data collection to validated treatment rankings, presented as both scientific methodology and implementation blueprint for next-generation regulatory systems.

Keywords: pharmacovigilance, real-world evidence, N-of-1 trials, pragmatic trials, causal inference, Bradford Hill criteria, treatment effects, validated outcome labels, comparative effectiveness, precision medicine

2 System Overview: From Methodology to Product

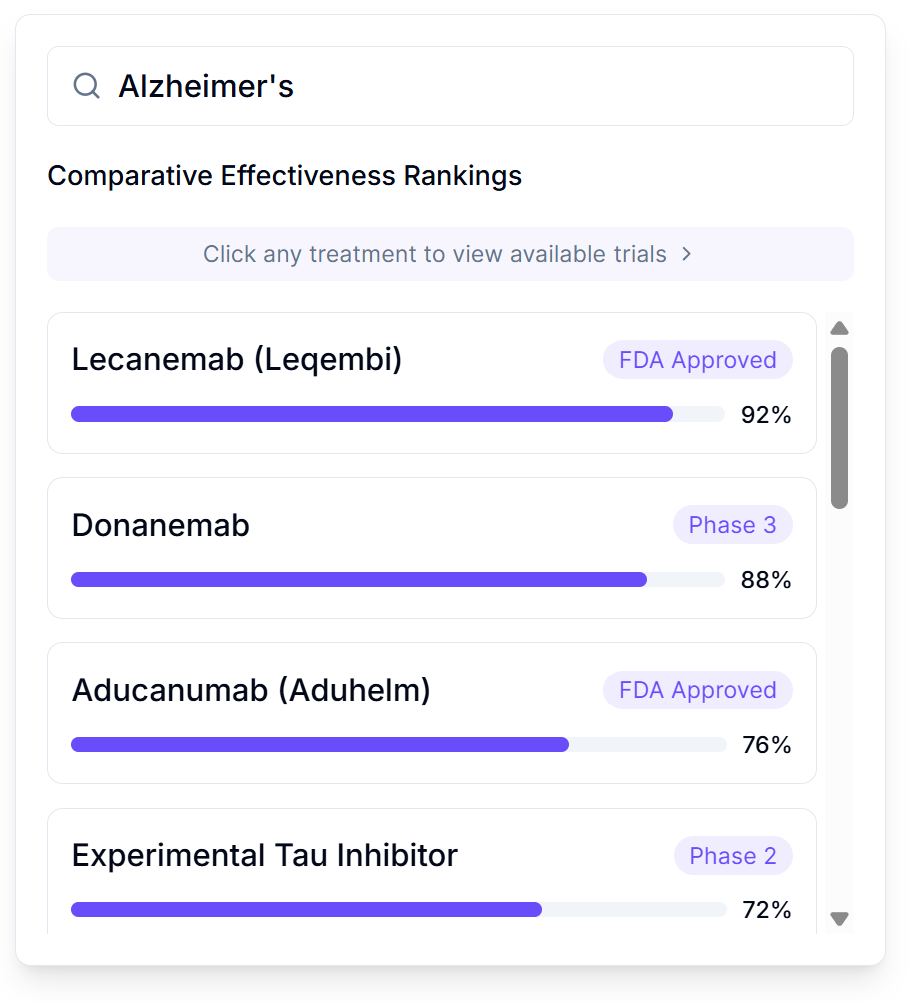

This paper describes the statistical methodology powering a patient-facing platform best understood as “Consumer Reports for drugs” - a searchable database where patients can look up any condition and see every treatment ranked by real-world effectiveness, with quantitative outcome labels showing exactly what happened to people who tried each option.

2.1 What Patients See

When a patient searches for their condition, they see:

- Treatment Rankings: Every option (FDA-approved drugs, supplements, lifestyle interventions, experimental treatments) ranked by effect size from real patient data

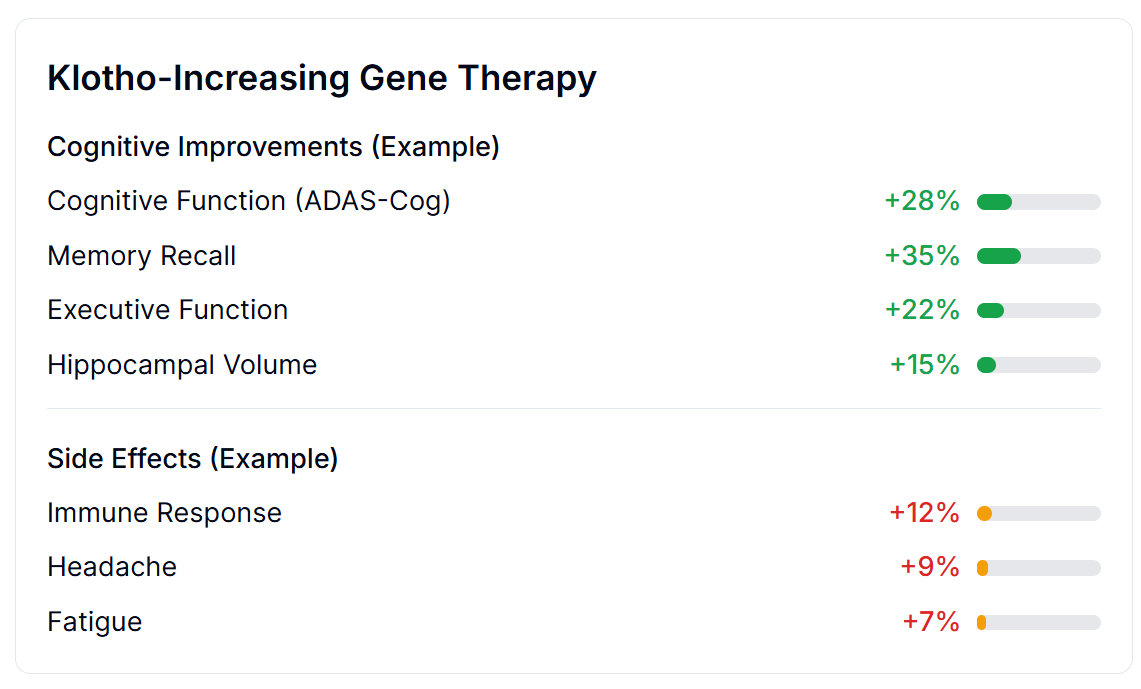

- Outcome Labels: “Nutrition facts for drugs” showing percent improvement, side effect rates, and sample sizes - not marketing claims

- Trial Access: One-click enrollment in available trials, from home, via any device

- Personalized Predictions: Based on their health data, which treatments work best for people like them

2.2 What Companies See

Any company - pharmaceutical, supplement, food, or intervention - can register a treatment in minutes at zero cost:

- Instant Registration: No approval bottleneck; treatment appears in search results immediately

- Zero Trial Cost: Patients pay for treatment (covering manufacturing); the platform handles data collection and analysis

- Automatic Liability Coverage: Built into the platform

- Free Clinical Data: Every patient who tries the treatment generates outcome data worth $41K (95% CI: $20K-$120K)/patient in traditional trials

2.3 Where This Methodology Fits

The Predictor Impact Score (PIS) described in this paper is the engine that powers treatment rankings. It transforms raw patient data into the ranked, quantified outcome labels that patients and clinicians use to make decisions. The two-stage pipeline ensures that:

- Stage 1 (this methodology) generates treatment rankings from millions of real-world observations at ~$0.100 (95% CI: $0.030-$1.00)/patient

- Stage 2 (pragmatic trials) confirms causation for high-priority signals at ~$500 (95% CI: $400-$2.50K)/patient

The result is a self-improving system where every patient’s experience helps the next patient make better decisions - transforming the current bottleneck of 1.90M patients/year (95% CI: 1.50M patients/year-2.30M patients/year) annual trial participants into a platform where anyone can contribute to medical knowledge.

For the complete user-facing vision, see A Decentralized Framework for Drug Assessment.

3 Introduction

3.1 The Human Cost of the Current System

Every year, 55.0M deaths/year (95% CI: 46.6M deaths/year-63.2M deaths/year) people die from diseases for which treatments exist or could exist. The tragedy is not that we lack medical knowledge. It’s that our system for generating and validating that knowledge operates at a fraction of its potential capacity.

Consider: a treatment that could save lives today takes an average of 8.2 years (95% CI: 4.85 years-11.5 years) to complete Phase 2-4 clinical trials after initial discovery. During this delay, people die waiting. Since 1962, regulatory testing delays for drugs that were eventually approved have contributed to an estimated 98.4M deaths (95% CI: 58.2M deaths-138M deaths) preventable deaths, more than all wars and conflicts of the 20th century combined.

This is not an argument against safety testing. It is an argument for better safety testing: faster, cheaper, more comprehensive, and continuously updated with real-world evidence rather than static pre-market snapshots.

The framework presented here could eliminate this efficacy lag for existing treatments while simultaneously enabling continuous discovery of new therapeutic relationships. The technology exists. The data exists. What remains is the institutional will to deploy it.

3.2 The Pharmacovigilance Gap

Modern pharmacovigilance (the science of detecting, assessing, and preventing adverse effects of pharmaceutical products) faces fundamental limitations:

Spontaneous Reporting Systems (e.g., FDA FAERS, EU EudraVigilance):

- Estimated 1-10% of adverse events are reported12

- No denominator data (cannot calculate incidence rates)

- Cannot quantify effect sizes or establish causality

- Significant reporting lag (months to years)

- Subject to stimulated reporting and notoriety bias

Pre-Market Clinical Trials:

- Limited sample sizes (typically hundreds to low thousands)

- Short duration (weeks to months)

- Homogeneous populations (exclusion criteria eliminate comorbidities)

- Controlled conditions unlike real-world use

- Cannot detect rare or delayed adverse events

- Cost: Average Phase III trial costs $20M and takes 3+ years4

Post-Market Studies:

- Expensive and time-consuming

- Often industry-sponsored with potential conflicts

- Limited to specific questions rather than comprehensive monitoring

3.3 The Real-World Data Opportunity

The past decade has seen explosive growth in patient-generated health data:

- Wearable devices: 500+ million users globally tracking sleep, activity, heart rate13

- Health apps: Symptom trackers, mood journals, medication reminders

- Connected health platforms: Comprehensive longitudinal health records

- Patient-reported outcomes: Systematic symptom and quality-of-life tracking

This data is characterized by:

- Longitudinal structure: Repeated measurements over months to years

- Natural variation: Patients modify treatments without experimental control

- Real-world conditions: Actual usage patterns, not controlled settings

- Scale: Millions of potential participants

3.4 Our Contribution

We present a framework that transforms real-world health data into actionable pharmacovigilance intelligence:

- Quantitative Outcome Labels: For each treatment, generate effect sizes (percent change from baseline) for all measured outcomes

- Treatment Rankings: Rank treatments by efficacy and safety within therapeutic categories

- Automated Signal Detection: Identify safety concerns (negative correlations) and efficacy signals (positive correlations)

- Bradford Hill Integration: Composite scoring that operationalizes causal inference criteria14,15

- Scalable Implementation: Analyze millions of treatment-outcome pairs automatically

This is not a replacement for RCTs but a complement, providing continuous, population-scale monitoring that can:

- Generate hypotheses for experimental validation

- Detect signals missed by spontaneous reporting

- Quantify effects that RCTs can only describe qualitatively

- Enable personalized benefit-risk assessment

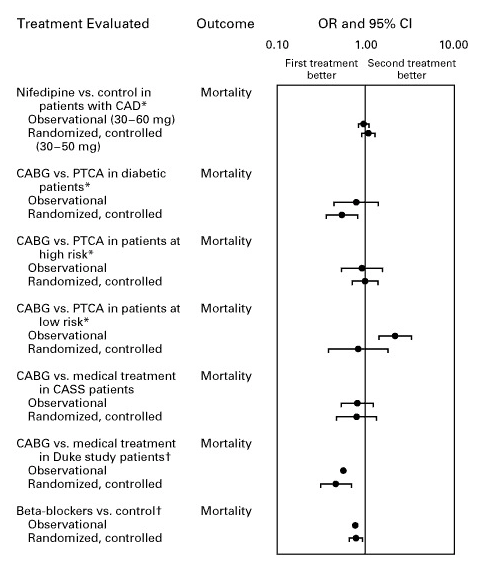

Multiple meta-analyses demonstrate that well-designed observational studies produce effect sizes concordant with randomized controlled trials, supporting the validity of real-world evidence for hypothesis generation:

4 Data Collection and Integration

4.1 Data Sources

Our framework integrates data from multiple sources, each contributing different variable types:

| Source Category | Examples | Data Types |

|---|---|---|

| Wearables | Fitbit, Apple Watch, Oura Ring, Garmin | Sleep, steps, heart rate, HRV |

| Health Apps | Symptom trackers, mood journals | Symptoms, mood, energy, pain |

| Medication Trackers | Medisafe, MyTherapy | Drug intake, dosage, timing |

| Diet Trackers | MyFitnessPal, Cronometer | Foods, nutrients, calories |

| Lab Integrations | Quest, LabCorp APIs | Biomarkers, blood tests |

| EHR Connections | FHIR-enabled systems | Diagnoses, prescriptions, vitals |

| Manual Entry | Custom tracking | Any user-defined variable |

| Environmental | Weather APIs, air quality | Temperature, humidity, pollution |

4.2 Variable Ontology

Variables are organized into semantic categories that inform default processing parameters:

| Category | Examples | Onset Delay | Duration | Filling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Drugs, supplements | 30 min | 24 hours | Zero |

| Foods | Diet, beverages | 30 min | 10 days | Zero |

| Symptoms | Pain, fatigue, nausea | 0 | 24 hours | None |

| Emotions | Mood, anxiety, depression | 0 | 24 hours | None |

| Vital Signs | Blood pressure, glucose | 0 | 24 hours | None |

| Sleep | Duration, quality, latency | 0 | 24 hours | None |

| Physical Activity | Steps, exercise, calories burned | 0 | 24 hours | None |

| Environment | Weather, air quality, allergens | 0 | 24 hours | None |

| Physique | Weight, body fat, measurements | 0 | 7 days | None |

4.3 Measurement Structure

Each measurement includes:

Measurement {

variable_id: int // Reference to variable definition

user_id: int // Anonymized participant identifier

value: float // Numeric measurement value

unit_id: int // Standardized unit reference

start_time: timestamp // When measurement was taken

source_id: int // Data source for provenance

note: string (optional) // User annotation

}4.4 Unit Standardization

All measurements are converted to standardized units for cross-source compatibility:

- Weights → kilograms

- Distances → meters

- Temperatures → Celsius

- Dosages → milligrams

- Durations → seconds

- Percentages → 0-100 scale

- Ratings → 1-5 scale (normalized)

5 Mathematical Framework

The short version: We track what people take (treatments, supplements, foods) and how they feel (symptoms, mood, energy) over time. Then we look for patterns: “When people take more of X, does Y get better or worse?” We account for the fact that treatments take time to work (onset delay) and their effects fade (duration of action). The math below makes this rigorous.

5.1 Data Structure

For each participant \(i \in \{1, ..., N\}\), we observe time series of predictor variable \(P\) (e.g., treatment) and outcome variable \(O\) (e.g., symptom):

\[P_i = \{(t_{i,1}^P, p_{i,1}), (t_{i,2}^P, p_{i,2}), ..., (t_{i,n_i}^P, p_{i,n_i})\}\]

\[O_i = \{(t_{i,1}^O, o_{i,1}), (t_{i,2}^O, o_{i,2}), ..., (t_{i,m_i}^O, o_{i,m_i})\}\]

where \(t\) denotes timestamp, \(p\) denotes predictor measurements, and \(o\) denotes outcome measurements. Critically, timestamps need not be aligned. Our framework handles asynchronous, irregular sampling.

5.2 Temporal Alignment

5.2.1 3.2.1 Onset Delay and Duration of Action

Treatments do not produce immediate effects. We define:

- Onset delay \(\delta\): Time lag before treatment produces observable effect

- Duration of action \(\tau\): Time window over which effect persists

Constraints: \[0 \leq \delta \leq 8{,}640{,}000 \text{ seconds (100 days)}\] \[600 \leq \tau \leq 7{,}776{,}000 \text{ seconds (90 days)}\]

5.2.2 3.2.2 Outcome Window Calculation

For a predictor measurement at time \(t\), we associate it with outcome measurements in the window:

\[W(t) = \{t_j : t + \delta \leq t_j \leq t + \delta + \tau\}\]

The aligned outcome value is computed as the mean:

\[\bar{o}(t) = \frac{1}{|W(t)|} \sum_{t_j \in W(t)} o_j\]

5.3 Pair Generation Strategies

We employ two complementary strategies depending on variable characteristics:

5.3.1 3.3.1 Outcome-Based Pairing (Predictor has Filling Value)

When the predictor has a filling value (e.g., zero for “not taken”), we create one pair per outcome measurement:

For each outcome measurement (t_o, o):

window_end = t_o - δ

window_start = window_end - τ + 1

predictor_values = measurements in [window_start, window_end]

if predictor_values is empty:

predictor_value = filling_value // e.g., 0

else:

predictor_value = mean(predictor_values)

create_pair(predictor_value, o)5.3.2 3.3.2 Predictor-Based Pairing (No Filling Value)

When the predictor has no filling value, we create one pair per predictor measurement:

For each predictor measurement (t_p, p):

window_start = t_p + δ

window_end = window_start + τ - 1

outcome_values = measurements in [window_start, window_end]

if outcome_values is empty:

skip this pair

else:

outcome_value = mean(outcome_values)

create_pair(p, outcome_value)5.4 Filling Value Logic

5.4.1 3.4.1 Filling Types

| Type | Description | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Zero | Missing = 0 | Treatments (assume not taken) |

| Value | Missing = specific constant | Known default states |

| None | No imputation | Continuous outcomes |

| Interpolation | Linear interpolation | Slowly-changing variables |

5.4.2 3.4.2 Temporal Boundaries

To prevent spurious correlations from extended filling periods:

- Earliest filling time: First recorded measurement (tracking start)

- Latest filling time: Last recorded measurement (tracking end)

Pairs outside these boundaries are excluded. This prevents filling zeros for a treatment before the participant started tracking it.

5.4.3 3.4.3 Conservative Bias

Our filling strategy is deliberately conservative:

- Zero-filling for treatments assumes non-adherence when no measurement exists

- This biases toward null findings (attenuated correlations) rather than false positives

- True effects must overcome this conservative bias to appear significant

5.5 Baseline Definition and Outcome Estimation

5.5.1 3.5.1 Within-Subject Comparison

For each participant \(i\), we compute the mean predictor value:

\[\bar{p}_i = \frac{1}{n_i} \sum_{j=1}^{n_i} p_{i,j}\]

We partition measurements into baseline and follow-up periods:

\[\text{Baseline}_i = \{(p, o) : p < \bar{p}_i\}\] \[\text{Follow-up}_i = \{(p, o) : p \geq \bar{p}_i\}\]

This creates a natural within-subject comparison:

- Baseline: Periods of below-average predictor exposure

- Follow-up: Periods of above-average predictor exposure

5.5.2 3.5.2 Outcome Means

\[\mu_{\text{baseline},i} = \mathbb{E}[o \mid p < \bar{p}_i]\] \[\mu_{\text{follow-up},i} = \mathbb{E}[o \mid p \geq \bar{p}_i]\]

5.6 Percent Change from Baseline

The primary effect size metric:

\[\Delta_i = \frac{\mu_{\text{follow-up},i} - \mu_{\text{baseline},i}}{\mu_{\text{baseline},i}} \times 100\]

Advantages:

- Interpretability: “15% reduction in pain” is intuitive

- Scale invariance: Enables comparison across different outcome measures

- Clinical relevance: Standard metric in medical literature

- Regulatory familiarity: FDA uses percent change in efficacy assessments

5.7 Correlation Coefficients

We compute both parametric and non-parametric measures:

5.7.1 3.7.1 Pearson Correlation (Linear Relationships)

\[r_{\text{Pearson}} = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^{n}(p_j - \bar{p})(o_j - \bar{o})}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=1}^{n}(p_j - \bar{p})^2} \cdot \sqrt{\sum_{j=1}^{n}(o_j - \bar{o})^2}}\]

5.7.2 3.7.2 Spearman Rank Correlation (Monotonic Relationships)

\[r_{\text{Spearman}} = 1 - \frac{6 \sum_{j=1}^{n} d_j^2}{n(n^2 - 1)}\]

where \(d_j = \text{rank}(p_j) - \text{rank}(o_j)\).

5.7.3 3.7.3 Forward and Reverse Correlations

We compute both:

- Forward: \(P \to O\) (predictor predicts outcome)

- Reverse: \(O \to P\) (outcome predicts predictor)

If reverse correlation is stronger, this suggests:

- Reverse causality (symptom drives treatment-seeking)

- Confounding by indication

- Bidirectional relationship

5.8 Z-Score Normalization

To assess effect magnitude relative to natural variability:

\[z = \frac{|\Delta|}{\text{RSD}_{\text{baseline}}}\]

where relative standard deviation:

\[\text{RSD}_{\text{baseline}} = \frac{\sigma_{\text{baseline}}}{\mu_{\text{baseline}}} \times 100\]

Interpretation: \(z > 2\) indicates \(p < 0.05\) under normality, meaning the observed effect exceeds typical baseline fluctuation.

5.9 Statistical Significance

Two-tailed t-test for correlation significance:

\[t = \frac{r\sqrt{n-2}}{\sqrt{1-r^2}}\]

with \(n-2\) degrees of freedom. Reject null hypothesis (\(H_0: \rho = 0\)) at \(\alpha = 0.05\) when:

\[|t| > t_{\text{critical}}(n-2, \alpha/2)\]

5.10 Hyperparameter Optimization

The onset delay \(\delta^*\) and duration of action \(\tau^*\) are selected to maximize correlation coefficient strength:

\[(\delta^*, \tau^*) = \underset{\delta, \tau}{\text{argmax}} \; |r(\delta, \tau)|\]

Search Strategy: 1. Initialize with category defaults (e.g., 30 min onset, 24 hr duration for drugs) 2. Grid search over physiologically plausible ranges 3. Select parameters yielding strongest correlation coefficient

Overfitting Mitigation:

- Restrict search to category-appropriate ranges

- Require minimum sample size before optimization

- Report both optimized and default-parameter results

6 Population Aggregation

6.1 Individual to Population

For population-level estimates, aggregate across \(N\) participants:

\[\bar{r} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} r_i\]

\[\bar{\Delta} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \Delta_i\]

6.2 Standard Error and Confidence Intervals

\[\text{SE}_{\bar{r}} = \frac{\sigma_r}{\sqrt{N}}\]

\[\text{CI}_{95\%} = \bar{r} \pm 1.96 \cdot \text{SE}_{\bar{r}}\]

6.3 Heterogeneity Assessment

Between-participant variance:

\[\sigma^2_{\text{between}} = \text{Var}(r_i)\]

High heterogeneity suggests:

- Subgroup effects (responders vs. non-responders)

- Interaction with unmeasured factors

- Need for personalized analysis

7 Data Quality Requirements

7.1 Minimum Thresholds

| Requirement | Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor value changes | \(\geq 5\) | Ensures sufficient variance |

| Outcome value changes | \(\geq 5\) | Ensures sufficient variance |

| Overlapping pairs | \(\geq 30\) | Central limit theorem |

| Baseline fraction | \(\geq 10\%\) | Adequate baseline |

| Follow-up fraction | \(\geq 10\%\) | Adequate predictor exposure |

| Processed daily measurements | \(\geq 4\) | Minimum data density |

7.2 Variance Validation

Before computing variable relationships, validate sufficient variance:

\[\text{changes}(X) = \sum_{j=1}^{n-1} \mathbb{1}[x_j \neq x_{j+1}]\]

If \(\text{changes}(P) < 5\) or \(\text{changes}(O) < 5\), abort with InsufficientVarianceException.

7.3 Outcome Value Spread

\[\text{spread}_O = \max(O) - \min(O)\]

Variable relationships with zero spread are undefined and excluded.

8 Predictor Impact Score

The short version: Not all correlations are created equal. If we observe that “people who take Drug X report less pain,” how confident should we be? The Predictor Impact Score (PIS) answers this by combining: (1) how strong is the relationship, (2) how many people show it, (3) does the drug come before the improvement (not after), and (4) is there a dose-response pattern. High PIS = worth investigating in a clinical trial. Low PIS = probably noise.

The Predictor Impact Score (PIS) is a composite metric that quantifies treatment-outcome relationship strength from patient health data, operationalizing Bradford Hill causality criteria to prioritize drug effects for clinical trial validation. It integrates correlation strength, statistical significance, effect magnitude, and multiple Bradford Hill criteria into a single interpretable score. Higher scores indicate predictors with greater, more reliable impact on the outcome.

Citation format: When citing this metric in academic work, use “Predictor Impact Score” with reference to this methodology document.

8.1 What Makes the Predictor Impact Score Novel

Unlike simple correlation coefficients, PIS addresses fundamental limitations of observational analysis:

Sample size agnosticism: Raw correlations don’t account for whether N=10 or N=10,000. PIS incorporates saturation functions that weight evidence accumulation.

Temporal ambiguity: Correlations can’t distinguish A→B from B→A. PIS includes a temporality factor comparing forward vs. reverse correlations.

Effect magnitude blindness: Statistical significance ≠ practical significance. PIS incorporates z-scores to assess effect magnitude relative to baseline variability.

Isolated metrics: Traditional analysis reports correlation, p-value, and effect size separately. PIS integrates them into a single prioritization metric aligned with Bradford Hill criteria.

The Predictor Impact Score is not a causal proof. It’s a principled heuristic for ranking which predictor-outcome relationships warrant further investigation, including experimental validation.

8.2 User-Level Predictor Impact Score

For individual participant (N-of-1) analyses, we compute:

\[\text{PIS}_{\text{user}} = |r| \cdot S \cdot \phi_z \cdot \phi_{\text{temporal}} \cdot f_{\text{interest}} + \text{PIS}_{\text{agg}}\]

Where:

- \(|r|\) = absolute value of the correlation coefficient (strength)

- \(S\) = statistical significance (1 - p-value)

- \(\phi_z\) = normalized z-score factor (effect magnitude)

- \(\phi_{\text{temporal}}\) = temporality factor (forward vs. reverse causation)

- \(f_{\text{interest}}\) = interest factor (penalizes spurious variable pairs)

- \(\text{PIS}_{\text{agg}}\) = population-level aggregate score (provides context from broader population)

8.3 Aggregate (Population-Level) Predictor Impact Score

For population-level analyses aggregated across multiple participants:

\[\text{PIS}_{\text{agg}} = |r_{\text{forward}}| \cdot w \cdot \phi_{\text{users}} \cdot \phi_{\text{pairs}} \cdot \phi_{\text{change}} \cdot \phi_{\text{gradient}}\]

Where:

- \(|r_{\text{forward}}|\) = absolute forward Pearson correlation coefficient (strength)

- \(w\) = weighted average of community votes on plausibility

- \(\phi_{\text{users}} = 1 - e^{-N / N_{\text{sig}}}\) (user saturation, \(N_{\text{sig}} = 10\))

- \(\phi_{\text{pairs}} = 1 - e^{-n / n_{\text{sig}}}\) (pair saturation, \(n_{\text{sig}}\) = significant pairs threshold)

- \(\phi_{\text{change}} = 1 - e^{-\Delta_{\text{spread}} / \Delta_{\text{sig}}}\) (change spread saturation)

- \(\phi_{\text{gradient}}\) = biological gradient coefficient (dose-response)

The saturation functions asymptotically approach 1 as sample sizes increase, reflecting that consistent findings across more participants strengthen causal inference.

8.4 Z-Score and Effect Magnitude Factor

The z-score quantifies the magnitude of the outcome change relative to baseline variability:

\[z = \frac{|\Delta\%_{\text{baseline}}|}{\text{RSD}_{\text{baseline}}}\]

Where:

- \(\Delta\%_{\text{baseline}}\) = percent change from baseline (see below)

- \(\text{RSD}_{\text{baseline}}\) = relative standard deviation of outcome during baseline period

A z-score > 2 indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05), meaning the observed change is unlikely due to random variation.

The normalized z-score factor incorporates effect magnitude into the PIS score:

\[\phi_z = \frac{|z|}{|z| + z_{\text{ref}}}\]

Where \(z_{\text{ref}} = 2\) (the conventional significance threshold). This saturating function:

- Approaches 0 for negligible effects (z → 0)

- Equals 0.5 at the significance threshold (z = 2)

- Approaches 1 for very large effects (z → ∞)

8.5 Temporality Factor

The temporality factor quantifies evidence that the predictor precedes and causes the outcome (rather than reverse causation):

\[\phi_{\text{temporal}} = \frac{|r_{\text{forward}}|}{|r_{\text{forward}}| + |r_{\text{reverse}}|}\]

Where:

- \(r_{\text{forward}}\) = correlation when predictor precedes outcome (P → O)

- \(r_{\text{reverse}}\) = correlation when outcome precedes predictor (O → P)

This factor:

- Equals 0.5 when forward and reverse correlations are equal (ambiguous causality)

- Approaches 1 when forward correlation dominates (supports predictor → outcome)

- Approaches 0 when reverse correlation dominates (suggests reverse causation or confounding by indication)

8.6 Percent Change from Baseline

The primary effect size metric expressing treatment impact:

\[\Delta\%_{\text{baseline}} = \frac{\bar{O}_{\text{follow-up}} - \bar{O}_{\text{baseline}}}{\bar{O}_{\text{baseline}}} \times 100\]

Where:

- \(\bar{O}_{\text{follow-up}}\) = mean outcome value during follow-up period (after predictor exposure)

- \(\bar{O}_{\text{baseline}}\) = mean outcome value during baseline period (before predictor exposure)

For outcomes measured in percentages or with zero baseline, we use absolute change instead: \[\Delta_{\text{abs}} = \bar{O}_{\text{follow-up}} - \bar{O}_{\text{baseline}}\]

8.7 Statistical Significance

The statistical significance component captures confidence in the relationship:

\[S = 1 - p\]

Where \(p\) is the p-value from the correlation significance test. Higher values indicate greater confidence that the observed relationship is not due to chance.

8.8 Interest Factor

The interest factor \(f_{\text{interest}}\) penalizes likely spurious or uninteresting variable pairs:

\[f_{\text{interest}} = f_P \cdot f_O \cdot f_{\text{pair}}\]

Where:

- \(f_P\) = predictor interest factor (reduced for test variables, apps, addresses)

- \(f_O\) = outcome interest factor (reduced for non-outcome categories)

- \(f_{\text{pair}}\) = pair appropriateness (reduced for illogical category combinations)

8.9 Additional Data Quality Components

Skewness Coefficient (penalizes non-normal distributions): \[\phi_{\text{skew}} = \frac{1}{1 + \gamma_{P}^2} \cdot \frac{1}{1 + \gamma_{O}^2}\]

Kurtosis Coefficient (penalizes heavy tails): \[\phi_{\text{kurt}} = \frac{1}{1 + \kappa_{P}^2} \cdot \frac{1}{1 + \kappa_{O}^2}\]

Biological Gradient (dose-response relationship): \[\phi_{\text{gradient}} = \left(\frac{\bar{p}_{\text{high}} - \bar{p}}{\sigma_P} - \frac{\bar{p}_{\text{low}} - \bar{p}}{\sigma_P}\right)^2\]

Measures the standardized difference between predictor values that predict high vs. low outcomes.

8.10 Bradford Hill Criteria Mapping

The PIS operationalizes six of the nine Bradford Hill criteria for causality16:

| Component | Formula | Bradford Hill Criterion | In PIS Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\|r\|\) | Correlation magnitude | Strength | Yes (direct) |

| \(\phi_z\) | Normalized z-score | Strength (effect magnitude) | Yes (user-level) |

| \(\Delta\%\) | Percent change from baseline | Strength (clinical significance) | Yes (via \(\phi_z\)) |

| \(\phi_{\text{users}}, \phi_{\text{pairs}}\) | Sample saturation | Consistency | Yes (aggregate) |

| \(\phi_{\text{gradient}}\) | Dose-response coefficient | Biological Gradient | Yes (aggregate) |

| \(w\) | Weighted community votes | Plausibility | Yes (aggregate) |

| \(f_{\text{interest}}\) | Category appropriateness | Specificity | Yes (user-level) |

| \(\phi_{\text{temporal}}\) | Forward/reverse ratio | Temporality | Yes (user-level) |

| \(\delta > 0\) | Onset delay requirement | Temporality | Enforced in design |

8.11 Interpreting Predictor Impact Scores

PIS scores range from 0 to approximately 1 (though values slightly above 1 are possible with very strong evidence). Guidelines for interpretation:

| PIS Range | Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 0.5 | Strong evidence | High priority for RCT validation |

| 0.3 - 0.5 | Moderate evidence | Consider for experimental investigation |

| 0.1 - 0.3 | Weak evidence | Monitor for additional data |

| < 0.1 | Insufficient evidence | Low priority; may be noise |

Important caveats:

- These thresholds are preliminary and should be validated against RCT outcomes

- PIS is relative, not absolute. Use it for prioritization, not proof.

- High PIS does not guarantee causation; low PIS does not rule it out

- Context matters: a PIS of 0.2 for a novel relationship may be more interesting than 0.5 for a known one

8.12 Optimal Daily Value for Precision Dosing

A key output of our analysis is the optimal daily value, the predictor value that historically precedes the best outcomes. This enables personalized, precision dosing recommendations.

8.12.1 6.11.1 Value Predicting High Outcome

The Value Predicting High Outcome (\(V_{\text{high}}\)) is the average predictor value observed when the outcome exceeds its mean:

\[V_{\text{high}} = \frac{1}{|H|} \sum_{(p, o) \in H} p\]

Where:

- \(H = \{(p, o) : o > \bar{O}\}\) is the set of predictor-outcome pairs where outcome exceeds its average

- \(\bar{O}\) = mean outcome value across all pairs

- \(p\) = predictor (cause) value for each pair

Calculation Process: 1. Compute the average outcome value (\(\bar{O}\)) across all predictor-outcome pairs 2. Filter pairs to include only those where outcome > \(\bar{O}\) (the “high effect” pairs) 3. Calculate the mean predictor value across these high-effect pairs

8.12.2 6.11.2 Value Predicting Low Outcome

The Value Predicting Low Outcome (\(V_{\text{low}}\)) is the average predictor value observed when the outcome is below its mean:

\[V_{\text{low}} = \frac{1}{|L|} \sum_{(p, o) \in L} p\]

Where:

- \(L = \{(p, o) : o < \bar{O}\}\) is the set of predictor-outcome pairs where outcome is below its average

8.12.3 6.11.3 Grouped Optimal Values

For interpretability, we also calculate grouped optimal values that map to common dosing intervals:

- Grouped Value Predicting High Outcome: The nearest grouped predictor value (e.g., rounded to typical dosing units) to \(V_{\text{high}}\)

- Grouped Value Predicting Low Outcome: The nearest grouped predictor value to \(V_{\text{low}}\)

This allows recommendations like “400mg of Magnesium” rather than “412.7mg of Magnesium.”

8.12.4 6.11.4 Precision Dosing Recommendations

These optimal values enable personalized recommendations:

For Positive Valence Outcomes (where higher is better, e.g., energy, sleep quality): > “Your [Outcome] was highest after [Grouped Value Predicting High Outcome] of [Predictor] over the previous [Duration of Action].” > > Example: “Your Sleep Quality was highest after 400mg of Magnesium over the previous 24 hours.”

For Negative Valence Outcomes (where lower is better, e.g., pain, anxiety): > “Your [Outcome] was lowest after [Grouped Value Predicting Low Outcome] of [Predictor] over the previous [Duration of Action].” > > Example: “Your Anxiety Severity was lowest after 100mg of Sertraline over the previous 24 hours.”

8.12.5 6.11.5 Mathematical Relationship to Biological Gradient

The optimal values are closely related to the biological gradient coefficient (\(\phi_{\text{gradient}}\)):

\[\phi_{\text{gradient}} = \left(\frac{V_{\text{high}} - \bar{P}}{\sigma_P} - \frac{V_{\text{low}} - \bar{P}}{\sigma_P}\right)^2\]

A larger separation between \(V_{\text{high}}\) and \(V_{\text{low}}\) indicates:

- Stronger dose-response relationship

- More reliable precision dosing recommendations

- Higher biological gradient coefficient

8.12.6 6.11.6 Clinical Applications

| Metric | Definition | Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|

| \(V_{\text{high}}\) | Avg predictor when outcome > mean | Optimal dose for positive outcomes |

| \(V_{\text{low}}\) | Avg predictor when outcome < mean | Dose to avoid for positive outcomes |

| \(V_{\text{high}} - V_{\text{low}}\) | Optimal value spread | Magnitude of dose-response effect |

Example Application: For a participant tracking Magnesium supplementation and Sleep Quality:

- \(V_{\text{high}}\) = 412mg → Grouped = 400mg (sleep quality highest after this dose)

- \(V_{\text{low}}\) = 127mg → Grouped = 125mg (sleep quality lowest after this dose)

- Recommendation: “Take approximately 400mg of Magnesium for optimal sleep quality”

8.12.7 6.11.7 Limitations

- Correlation ≠ Causation: Optimal values reflect associations, not guaranteed causal effects

- Individual Variation: Population optimal values may not be optimal for all individuals

- Context Dependence: Optimal values may vary by timing, combination with other factors

- Grouping Artifacts: Rounding to common doses may lose precision

Best Practice: Use optimal values as starting points for personal experimentation, not as definitive prescriptions.

8.12.8 6.11.8 Confidence Intervals for Optimal Values

Optimal values should be reported with uncertainty bounds to convey reliability:

\[\text{CI}_{V_{\text{high}}} = V_{\text{high}} \pm t_{\alpha/2} \cdot \frac{\sigma_{p|H}}{\sqrt{|H|}}\]

Where:

- \(\sigma_{p|H}\) = standard deviation of predictor values in high-outcome set \(H\)

- \(|H|\) = number of pairs in high-outcome set

- \(t_{\alpha/2}\) = critical t-value for desired confidence level

Interpretation Guidelines:

| CI Width (relative to mean) | Reliability | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| < 10% | High | Use as primary recommendation |

| 10-25% | Moderate | Present as range (e.g., “350-450mg”) |

| 25-50% | Low | Insufficient precision for dosing |

| > 50% | Very Low | Do not use for recommendations |

Example: If \(V_{\text{high}} = 400\text{mg}\) with 95% CI [380, 420], report: “Optimal dose: 400mg (95% CI: 380-420mg)”

8.12.9 6.11.9 Individual vs Population Optimal Values

Both individual and population optimal values are computed and stored. Guidelines for use:

| Scenario | Recommended Source | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| User has ≥50 paired measurements | Individual \(V_{\text{high}}\) | Sufficient personal data |

| User has 20-50 measurements | Weighted blend | \(0.5 \cdot V_{\text{user}} + 0.5 \cdot V_{\text{pop}}\) |

| User has <20 measurements | Population \(V_{\text{high}}\) | Insufficient personal data |

| User’s optimal differs >50% from population | Flag for review | May indicate unique response or data quality issue |

Blending Formula:

\[V_{\text{recommended}} = w \cdot V_{\text{user}} + (1-w) \cdot V_{\text{pop}}\]

Where \(w = \min(1, n_{\text{user}} / n_{\text{threshold}})\) with \(n_{\text{threshold}} = 50\) pairs.

8.12.10 6.11.10 Temporal Stability and Recalculation

Optimal values may drift over time due to:

- Physiological changes (age, weight, health status)

- Tolerance development

- Seasonal factors

- Lifestyle changes

Recalculation Policy:

| Trigger | Action |

|---|---|

| New measurements added | Recalculate after every 10 new pairs |

| Time elapsed | Recalculate monthly regardless of new data |

| Significant life change | User-triggered recalculation |

| Optimal value drift >20% | Alert user to potential change |

Rolling Window Option: For treatments where tolerance is expected, compute optimal values using only the most recent 90 days of data rather than all historical data.

Stability Metric: \[\text{Stability} = 1 - \frac{|V_{\text{high}}^{\text{current}} - V_{\text{high}}^{\text{previous}}|}{V_{\text{high}}^{\text{previous}}}\]

Stability < 0.8 (>20% change) triggers a notification to the user.

8.12.11 6.11.11 Edge Cases: Minimal Dose-Response

When \(V_{\text{high}} \approx V_{\text{low}}\), the predictor shows no clear dose-response relationship:

Detection Criterion: \[\frac{|V_{\text{high}} - V_{\text{low}}|}{\sigma_P} < 0.5\]

(Less than half a standard deviation apart)

Possible Interpretations: 1. Threshold effect: Any dose above zero works equally well 2. No effect: Predictor doesn’t influence outcome 3. Non-linear response: U-shaped or inverted-U curve not captured by simple high/low split 4. Insufficient variance: User takes similar doses, preventing detection

Handling:

- Do not display optimal value recommendations when dose-response is minimal

- Instead report: “No clear dose-response relationship detected for [Predictor] → [Outcome]”

- Flag for potential non-linear analysis in future versions

8.12.12 6.11.12 Validation of Optimal Values

The Critical Question: Do users who follow optimal value recommendations actually experience better outcomes than those who don’t?

Proposed Validation Study:

- Prospective A/B Test:

- Group A: Receives personalized optimal value recommendations

- Group B: Receives no recommendations (continues current behavior)

- Compare outcome trajectories over 30-90 days

- Retrospective Adherence Analysis:

- For users with established optimal values, calculate “adherence score”: \[\text{Adherence} = \frac{\text{Days within } \pm 20\% \text{ of } V_{\text{high}}}{\text{Total tracking days}}\]

- Correlate adherence with outcome improvement

Success Metrics:

- Users in top adherence quartile should show >15% better outcomes than bottom quartile

- Optimal value recommendations should outperform random dosing by >10%

Current Status: This validation has not been performed. Until validated, optimal values should be presented as “data-driven suggestions” rather than “clinically validated recommendations.”

8.13 Saturation Constant Rationale

The saturation constants (N_sig, n_sig, etc.) reflect pragmatic thresholds based on statistical and clinical considerations:

| Constant | Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| N_sig (users) | 10 | At N=10, user saturation ≈ 0.63. By N=30, ≈ 0.95. Reflects that consistency across 10+ individuals provides meaningful replication. |

| n_sig (pairs) | 100 | Central limit theorem suggests n≥30 for normality. We use 100 as the “strong evidence” threshold. |

| Δ_sig (change spread) | 10% | A 10% change is often considered clinically meaningful across many health outcomes. |

| z_ref | 2 | Corresponds to p < 0.05 under normality (the conventional significance threshold). |

These constants are not empirically optimized. Future work should: 1. Validate constants against known causal relationships (from RCTs) 2. Consider domain-specific thresholds (e.g., psychiatric vs. cardiovascular outcomes) 3. Implement sensitivity analyses to assess robustness to constant choices

8.14 Effect Following High vs Low Predictor Values

Beyond optimal values, we calculate the average outcome following different predictor levels to quantify dose-response relationships:

8.14.1 6.13.1 Average Outcome Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Average Outcome | Mean outcome across all pairs | Baseline outcome level |

| Average Outcome Following High Predictor | Mean outcome when predictor > mean | Outcome after high exposure |

| Average Outcome Following Low Predictor | Mean outcome when predictor < mean | Outcome after low exposure |

| Average Daily High Predictor | Mean predictor in upper 51% of spread | “High dose” value |

| Average Daily Low Predictor | Mean predictor in lower 49% of spread | “Low dose” value |

8.14.2 6.13.2 Calculation

\[\bar{O}_{\text{high}} = \mathbb{E}[O \mid P > \bar{P}]\] \[\bar{O}_{\text{low}} = \mathbb{E}[O \mid P \leq \bar{P}]\]

Where \(\bar{P}\) is the mean predictor value across all pairs.

Effect Size from High to Low Cause: \[\Delta_{\text{high-low}} = \frac{\bar{O}_{\text{high}} - \bar{O}_{\text{low}}}{\bar{O}_{\text{low}}} \times 100\]

This metric directly shows the percent difference in outcome between high and low predictor exposure periods.

8.15 Predictor Baseline and Treatment Averages

For treatment-response analysis, we distinguish between baseline (non-treatment) and treatment periods:

| Metric | Definition | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor Baseline Average Per Day | Average daily predictor during low-exposure periods | Typical non-treatment value |

| Predictor Treatment Average Per Day | Average daily predictor during high-exposure periods | Typical treatment dosage |

| Predictor Baseline Average Per Duration Of Action | Baseline cumulative over duration of action | For longer-acting effects |

| Predictor Treatment Average Per Duration Of Action | Treatment cumulative over duration of action | Cumulative treatment dose |

Example: For a user taking Magnesium supplements:

predictor_baseline_average_per_day= 50mg (days not supplementing, dietary only)predictor_treatment_average_per_day= 400mg (days actively supplementing)- This reveals the effective treatment dose vs. background exposure

8.16 Relationship Quality Filters

Not all statistically significant relationships are useful. We apply quality filters to prioritize actionable findings:

8.16.1 6.15.1 Filter Flags

| Flag | Description | Impact on Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor Is Controllable | User can directly modify this predictor (e.g., food, supplements) | Required for actionable recommendations |

| Outcome Is A Goal | Outcome is something users want to optimize (e.g., mood, energy) | Required for relevance |

| Plausibly Causal | Plausible biological mechanism exists | Increases confidence |

| Obvious | Relationship is already well-known (e.g., caffeine → alertness) | May deprioritize for discovery |

| Boring | Relationship unlikely to interest users | Filters from default views |

| Interesting Variable Category Pair | Category combination is typically meaningful (e.g., Treatment → Symptom) | Prioritizes for analysis |

8.16.2 6.15.2 Boring Relationship Definition

A relationship is marked boring = TRUE if ANY of:

- Predictor is not controllable AND outcome is not a goal

- Relationship could not plausibly be causal

- Confidence level is LOW

- Effect size is negligible (|Δ| < 1%)

- Relationship is trivially obvious

8.16.3 6.15.3 Usefulness and Causality Voting

Users can vote on individual relationships:

| Vote Type | Values | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Usefulness Vote | -1, 0, 1 | Whether knowledge of this relationship is useful |

| Causality Vote | -1, 0, 1 | Whether there’s a plausible causal mechanism |

Aggregate votes contribute to the PIS plausibility weight (\(w\)).

8.17 Variable Valence

Valence indicates whether higher values of a variable are inherently good, bad, or neutral:

| Valence | Meaning | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Higher is better | Energy, Sleep Quality, Productivity |

| Negative | Lower is better | Pain, Anxiety, Fatigue |

| Neutral | Direction depends on context | Heart Rate, Weight |

8.17.1 6.16.1 Impact on Interpretation

Valence affects how we interpret correlation direction:

| Predictor-Outcome Valence | Positive Correlation | Negative Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Positive → Positive | Both improve together | Trade-off |

| Positive → Negative | Predictor worsens outcome | Predictor improves outcome |

| Treatment → Negative Symptom | Side effect | Therapeutic effect |

Example: A positive correlation between Sertraline and Depression Severity is BAD (depression has negative valence, so lower is better). The same positive correlation between Sertraline and Energy would be GOOD.

8.18 Temporal Parameter Optimization

We optimize onset_delay (δ) and duration_of_action (τ) to find the temporal parameters that maximize correlation strength:

8.18.1 6.17.1 Stored Optimization Data

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Correlations Over Delays | Pearson r values for various onset delays |

| Correlations Over Durations | Pearson r values for various durations of action |

| Onset Delay With Strongest Pearson Correlation | Optimal δ value |

| Pearson Correlation With No Onset Delay | Baseline r for immediate effect |

| Average Forward Pearson Correlation Over Onset Delays | Mean r across all tested delays |

| Average Reverse Pearson Correlation Over Onset Delays | Mean reverse r across delays |

8.18.2 6.17.2 Optimization Grid

For each predictor-outcome pair, we test:

- Onset delays: 0, 30min, 1hr, 2hr, 4hr, 8hr, 12hr, 24hr, 48hr, 72hr…

- Durations: 1hr, 4hr, 12hr, 24hr, 48hr, 72hr, 1 week, 2 weeks…

The parameters yielding the strongest |r| are selected, subject to category-specific physiological constraints.

8.18.3 6.17.3 Overfitting Protection

To prevent spurious optimization: 1. Minimum pairs required: Only optimize if n > 50 pairs 2. Category constraints: Limit search to plausible ranges (e.g., caffeine onset < 2hr) 3. Report both: Show optimized AND default-parameter results 4. Consistency check: Compare forward vs reverse optimization

8.19 Spearman Rank Correlation

In addition to Pearson correlation, we compute Spearman rank correlation (forward_spearman_correlation_coefficient) for robustness:

\[r_s = 1 - \frac{6 \sum d_i^2}{n(n^2-1)}\]

Where \(d_i\) = difference in ranks for each pair.

Advantages over Pearson:

- Robust to outliers

- Captures monotonic (not just linear) relationships

- Less affected by skewed distributions

When to prefer Spearman:

- Outcome has skewed distribution (e.g., symptom severity with many zeros)

- Relationship is monotonic but non-linear (e.g., diminishing returns)

- Data contains outliers from measurement errors

9 Outcome Label Generation

9.1 Predictor Analysis Reports

For each outcome variable (e.g., Depression Severity), we generate comprehensive “outcome labels” showing:

- All predictors ranked by effect size

- Positive predictors (treatments/factors that improve the outcome)

- Negative predictors (treatments/factors that worsen the outcome)

- Effect sizes as percent change from baseline

- Confidence levels and sample sizes

9.2 Report Structure

Outcome Label: [Outcome Variable Name]

Population: N = [number] participants

Total Studies: [number] treatment-outcome pairs analyzed

POSITIVE EFFECTS (Treatments predicting IMPROVEMENT)

================================================

Rank | Treatment | Effect Size | 95% CI | N | Confidence

-----|-----------|-------------|--------|---|------------

1 | Treatment A | +23.5% | [18.2, 28.8] | 1,247 | High

2 | Treatment B | +18.2% | [12.1, 24.3] | 892 | High

3 | Treatment C | +12.7% | [8.3, 17.1] | 2,103 | High

...

NEGATIVE EFFECTS (Treatments predicting WORSENING)

=================================================

Rank | Treatment | Effect Size | 95% CI | N | Confidence

-----|-----------|-------------|--------|---|------------

1 | Treatment X | -15.3% | [-20.1, -10.5] | 567 | Medium

2 | Treatment Y | -8.7% | [-12.3, -5.1] | 1,892 | High

...

NO SIGNIFICANT EFFECT

=====================

[List of treatments with |Δ| < threshold or p > 0.05]9.3 Category-Specific Analysis

Reports are organized by predictor category:

- Treatments (Drugs, Supplements)

- Ranked by efficacy (positive Δ)

- Safety signals highlighted (negative Δ)

- Foods & Nutrients

- Dietary factors affecting outcome

- Lifestyle Factors

- Sleep, exercise, activities

- Environmental Factors

- Weather, pollution, allergens

- Comorbid Conditions

- Other symptoms/conditions as predictors

9.4 Verification Status

Each study is classified by verification status:

| Status | Icon | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Verified | ✓ | Up-voted by users; data reviewed and valid |

| Unverified | ? | Awaiting review |

| Flagged | ✗ | Down-voted; potential data quality issues |

9.5 Outcome Labels vs. FDA Drug Labels

Traditional FDA drug labels are per-drug documents that list qualitative adverse events and indications based on pre-market trials. They are static (updated infrequently), qualitative (“may cause drowsiness”), and organized around the drug rather than the patient’s condition.

Outcome Labels invert this paradigm: they are per-outcome documents that rank all treatments by quantitative effect size for a given health outcome. They are dynamic (updated continuously as data arrives), quantitative (“↓24.7% depression severity”), and organized around what the patient wants to optimize. This enables patients and clinicians to answer the question: “What works best for my condition?” This is a question traditional drug labels cannot answer.

9.6 Worked Example: Complete Outcome Label

The following shows a complete outcome label for depression, demonstrating how treatments are ranked by effect size with confidence intervals:

OUTCOME LABEL: Depression Severity

Based on 47,832 participants tracking depression outcomes Last updated: 2026-01-04 | Data period: 2020-2026

Treatments Improving Depression (ranked by effect size \(\Delta\))

| Rank | Treatment | Effect | 95% CI | N | PIS | Optimal Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exercise | −31.2% | [27.1, 35.3] | 12,847 | 0.67 | 45 min/day |

| 2 | Bupropion | −28.3% | [22.1, 34.5] | 2,847 | 0.54 | 300mg |

| 3 | Sertraline | −24.7% | [19.8, 29.6] | 5,123 | 0.51 | 100mg |

| 4 | Sleep (7-9 hrs) | −22.1% | [18.4, 25.8] | 31,204 | 0.48 | 8.2 hrs |

| 5 | Venlafaxine | −21.2% | [15.3, 27.1] | 1,892 | 0.44 | 150mg |

| 6 | Omega-3 | −18.9% | [14.2, 23.6] | 4,521 | 0.38 | 2000mg EPA+DHA |

| 7 | Meditation | −16.4% | [12.1, 20.7] | 8,932 | 0.35 | 20 min/day |

| 8 | Fluoxetine | −15.8% | [11.2, 20.4] | 3,456 | 0.33 | 40mg |

| 9 | Vitamin D | −12.3% | [8.7, 15.9] | 6,789 | 0.28 | 4000 IU |

| 10 | Social interaction | −11.7% | [8.2, 15.2] | 9,234 | 0.26 | 3+ hrs/day |

Treatments Worsening Depression (safety signals)

| Rank | Treatment | Effect | 95% CI | N | PIS | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alcohol (>2/day) | +23.4% | [18.9, 27.9] | 7,234 | 0.52 | Dose-dependent |

| 2 | Sleep deprivation | +19.8% | [15.2, 24.4] | 14,521 | 0.47 | <6 hrs/night |

| 3 | Social isolation | +15.2% | [11.3, 19.1] | 5,892 | 0.38 | <1 hr/day |

| 4 | Refined sugar | +8.7% | [5.2, 12.2] | 11,234 | 0.24 | >50g/day |

No Significant Effect (\(|\Delta| < 5\%\) or \(p > 0.05\)): Multivitamin, Probiotics, B-complex, Magnesium (for depression specifically), Ashwagandha, 5-HTP, SAMe, St. John’s Wort1

Legend: PIS = Predictor Impact Score (0-1 scale, higher = stronger evidence); Optimal Dose = \(V_{high}\) (predictor value associated with best outcomes)

Interpretation: This outcome label shows that for depression, exercise and sleep optimization rival or exceed pharmaceutical interventions in effect size, with stronger evidence bases (higher N). Bupropion and Sertraline lead among medications. The safety signals section highlights modifiable risk factors that worsen depression.

10 Treatment Ranking System

10.1 Within-Category Rankings

For each therapeutic category (e.g., Antidepressants), treatments are ranked by:

- Primary: Effect size (percent change from baseline)

- Secondary: Confidence level (High > Medium > Low)

- Tertiary: Sample size

10.2 Ranking Algorithm

For each treatment \(T\) in a therapeutic category, we compute a composite ranking score:

\[\text{RankScore}_T = \bar{\Delta}_T \times w_{\text{confidence}} \times \text{PIS}_T\]

where \(\bar{\Delta}_T\) is the mean effect size across participants, \(w_{\text{confidence}}\) is the confidence weight (see Table 3), and \(\text{PIS}_T\) is the Predictor Impact Score. Treatments are sorted by descending rank score.

10.3 Confidence Weighting

| Confidence Level | Weight (\(w\)) | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| High | 1.0 | \(p < 0.01\) OR \(N > 100\) OR pairs \(> 500\) |

| Medium | 0.7 | \(p < 0.05\) OR \(N > 10\) OR pairs \(> 100\) |

| Low | 0.4 | Meets minimum thresholds only |

10.4 Comparative Effectiveness Display

Table 4 illustrates how treatments within a therapeutic category are presented to users.

| Rank | Treatment | Effect (\(\Delta\)) | 95% CI | N | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bupropion 300mg | −28.3% | [22.1, 34.5] | 2,847 | High |

| 2 | Sertraline 100mg | −24.7% | [19.8, 29.6] | 5,123 | High |

| 3 | Venlafaxine 150mg | −21.2% | [15.3, 27.1] | 1,892 | High |

| 4 | Fluoxetine 40mg | −18.9% | [13.2, 24.6] | 3,456 | High |

11 Safety and Efficacy Quantification

11.1 Safety Signal Detection

Adverse Effect Identification: Safety signals are identified through (1) negative correlations between treatment and beneficial outcomes, and (2) positive correlations between treatment and harmful outcomes.

| Outcome | Effect (\(\Delta\)) | 95% CI | Plausibility | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | +18.3% | [12.1, 24.5] | High (known sedation) | Monitor |

| Nausea | +15.7% | [8.9, 22.5] | High (GI effects) | Monitor |

| Weight Gain | +8.2% | [4.1, 12.3] | Medium | Long-term monitoring |

| Anxiety | +6.5% | [2.1, 10.9] | Low (paradoxical) | Investigate |

11.2 Efficacy Signal Detection

Therapeutic Effect Identification: Efficacy signals are identified through (1) positive correlations between treatment and beneficial outcomes, and (2) negative correlations between treatment and harmful outcomes (symptom reduction).

| Outcome | Effect (\(\Delta\)) | 95% CI | Indication | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | −24.7% | [19.8, 29.6] | Primary | Strong |

| Anxiety | −18.2% | [12.3, 24.1] | Secondary | Strong |

| Sleep Quality | +15.3% | [10.1, 20.5] | Secondary | Moderate |

| Energy | +12.1% | [7.2, 17.0] | Secondary | Moderate |

11.3 Benefit-Risk Assessment

Net Clinical Benefit Score:

\[\text{NCB} = \sum_{i \in \text{benefits}} w_i \cdot |\Delta_i| - \sum_{j \in \text{risks}} w_j \cdot |\Delta_j|\]

where \(w\) represents importance weights assigned by clinical relevance.

Example: Sertraline 100mg Benefit-Risk Profile

| Benefits | Effect | Weight | Risks | Effect | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | −24.7% | 1.0 | Nausea | +8.3% | 0.3 |

| Anxiety | −18.2% | 0.8 | Insomnia | +5.1% | 0.4 |

| Sexual dysfunction | +12.7% | 0.5 |

Weighted Summary: Benefits = 39.26, Risks = 8.93, Net Clinical Benefit = +30.33 (favorable profile for depression/anxiety)

12 Addressing the Bradford Hill Criteria

The Bradford Hill criteria16 provide the foundational framework for assessing causation from observational data. This section details how our framework addresses each criterion.

12.1 Complete Criteria Mapping

| Criterion | How Addressed | Quantitative Metric | In PIS? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strength | Effect size magnitude | Pearson \(r\), \(\Delta\)% | Yes |

| Consistency | Cross-participant aggregation | \(N\), \(n\), SE, CI | Yes |

| Specificity | Category appropriateness | Interest factor | Yes |

| Temporality | Onset delay requirement | \(\delta > 0\) enforced | Yes |

| Biological Gradient | Dose-response analysis | Gradient coefficient | Yes |

| Plausibility | Community voting | Up/down votes | Yes |

| Coherence | Literature cross-reference | Narrative | No |

| Experiment | N-of-1 natural experiments | Study design | No |

| Analogy | Similar variable comparison | Narrative | No |

12.2 Quantitative Criteria Details

Strength:

- Reports Pearson \(r\) with classification (very strong: ≥0.8, strong: ≥0.6, moderate: ≥0.4, weak: ≥0.2, very weak: <0.2)

- Example: “There is a moderately positive (R = 0.45) relationship between Sertraline and Depression improvement.”

Consistency:

- Reports \(N\) participants, \(n\) paired measurements

- Notes that spurious associations naturally dissipate as participants modify behaviors based on non-replicating findings

Temporality:

- Onset delay \(\delta\) explicitly encodes treatment-to-effect lag

- Forward vs. reverse correlation comparison identifies potential reverse causality

Plausibility:

- Users vote on biological mechanism plausibility

- Weighted average contributes to ranking

- Crowd-sources expert and patient knowledge

13 Validation and Quality Assurance

13.1 User Voting System

Each study can receive user votes:

| Vote | Meaning | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Up-vote (👍) | Data appears valid, relationship plausible | Included in verified results |

| Down-vote (👎) | Data issues or implausible relationship | Flagged for review |

| No vote | Not yet reviewed | Included in unverified results |

13.2 Automated Quality Checks

Before inclusion in reports:

- Variance check: Minimum 5 value changes in both variables

- Sample size check: Minimum 30 paired measurements

- Baseline adequacy: ≥10% of data in baseline period

- Effect spread check: Non-zero outcome variance

- Temporal coverage: Adequate follow-up duration

13.3 Flagged Study Handling

Studies may be flagged for:

- Insufficient data

- Extreme outliers

- Implausible effect sizes (>200% change)

- Data entry errors

- Measurement device malfunctions

Flagged studies are:

- Excluded from primary rankings

- Available for review in separate section

- Can be un-flagged after data correction

14 Stage 2: Pragmatic Trial Confirmation

The short version: Observational data can find promising signals, but only randomized trials can prove causation. The good news: we don’t need expensive, slow traditional trials. The Oxford RECOVERY trial proved that “pragmatic” trials (simple randomization embedded in routine care) can validate treatments at 82x (95% CI: 50x-94.1x) lower cost and 10x faster. We use cheap observational analysis (Stage 1) to filter millions of possibilities down to the top candidates, then confirm the best ones with pragmatic trials (Stage 2). Result: validated treatment recommendations at a fraction of current cost.

The observational methodology described in Sections 1-11 generates ranked hypotheses about treatment-outcome relationships. While powerful for signal detection and hypothesis generation, observational data alone cannot establish causation due to unmeasured confounding. This section describes how pragmatic clinical trials serve as the confirmation layer, transforming promising observational signals into validated causal relationships.

14.1 The Two-Stage Pipeline

Our complete methodology operates as a two-stage pipeline:

| Stage | Method | Cost | Purpose | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Signal Detection | Aggregated N-of-1 observational analysis | ~$0.10/patient | Hypothesis generation | Ranked PIS signals |

| Stage 2: Causal Confirmation | Pragmatic randomized trials | ~$500 (95% CI: $400-$2.50K)/patient | Causation proof | Validated effect sizes |

This design leverages the complementary strengths of each approach:

- Stage 1 scales to millions of treatment-outcome pairs at minimal cost, identifying the most promising candidates

- Stage 2 applies experimental rigor to confirm causation for high-priority signals

14.2 Pragmatic Trial Methodology

Pragmatic trials differ fundamentally from traditional Phase III trials10:

| Dimension | Traditional Phase III | Pragmatic Trial (RECOVERY Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per patient | ||

| Time to results | 3-7 years | 3-6 months |

| Patient population | Homogeneous (strict exclusion) | Real-world (minimal exclusion) |

| Setting | Specialized research centers | Routine clinical care |

| Data collection | Extensive case report forms | Minimal essential outcomes |

| Randomization | Complex stratification | Simple 1:1 or 1:1:1 |

| Sample size | Hundreds to thousands | Thousands to tens of thousands |

The Oxford RECOVERY trial demonstrated this model’s effectiveness: 49,000 patients enrolled across 186 hospitals, 12 treatments evaluated, first life-saving result (dexamethasone) in 100 days, 1.00M lives (95% CI: 500k lives-2.00M lives) saved globally6.

14.3 Signal-to-Trial Prioritization

Not all observational signals warrant pragmatic trial confirmation. We propose a Trial Priority Score (TPS) combining:

\[TPS = PIS \times \sqrt{DALYs_{addressable}} \times \text{Novelty} \times \text{Feasibility}\]

Where:

- PIS: Predictor Impact Score from Stage 1 (higher = stronger signal)

- DALYs_{addressable}: Disease burden addressable by the treatment

- Novelty: Inverse of existing evidence (new signals prioritized)

- Feasibility: Practical considerations (drug availability, safety profile, cost)

Signals in the top 0.1-1% by TPS are candidates for pragmatic trial confirmation.

14.4 Comparative Effectiveness Randomization

For treatments already in clinical use, we employ comparative effectiveness designs following the ADAPTABLE trial model11:

- Embedded randomization: Randomization occurs within routine care visits

- Minimal disruption: Patients receive standard care with random assignment between active comparators

- Real-world endpoints: Primary outcomes are events captured in EHR (mortality, hospitalization, symptom resolution)

- Large simple design: Thousands of patients, minimal per-patient data collection

Example protocol for a high-PIS signal (Treatment A vs. Treatment B for Outcome X):

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Eligibility | Patients with Condition Y initiating treatment for Outcome X |

| Randomization | 1:1 to Treatment A vs. Treatment B |

| Primary endpoint | Change in Outcome X at 90 days |

| Data collection | Baseline characteristics (EHR), outcome at 90 days (patient-reported or EHR) |

| Sample size | 2,000 patients (1,000 per arm) |

| Cost | ~$1M total ($500 (95% CI: $400-$2.50K)/patient) |

| Timeline | 6-12 months |

14.5 Feedback Loop: Trial Results Improve Observational Models

Pragmatic trial results feed back to improve Stage 1 methodology:

- Calibration: Compare observational effect sizes to randomized effect sizes; develop correction factors

- Confounding identification: Trials where observational and randomized effects diverge identify confounders

- Subgroup discovery: Trial heterogeneity analysis identifies responder populations, improving PIS stratification

- Hyperparameter validation: Optimal onset delays and durations validated against experimental ground truth

This creates a learning health system where observational and experimental evidence continuously refine each other.

14.6 Output: Validated Outcome Labels

The two-stage pipeline produces validated outcome labels combining observational and experimental evidence. Table 9 shows the data elements captured for each treatment-outcome pair.

| Component | Field | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | Treatment | Intervention name and dose | Vitamin D 2000 IU |

| Outcome | Health outcome measured | Depression Severity | |

| Stage 1 (Observational) | \(\Delta_{obs}\) | Observational effect size | −12% |

| \(\text{CI}_{obs}\) | 95% confidence interval | [−15%, −9%] | |

| \(N_{obs}\) | Number of participants | 45,000 | |

| PIS | Predictor Impact Score | 0.72 | |

| Stage 2 (Experimental) | \(\Delta_{exp}\) | Randomized trial effect | −8% |

| \(\text{CI}_{exp}\) | Trial confidence interval | [−12%, −4%] | |

| \(N_{exp}\) | Trial participants | 3,000 | |

| Trial ID | Registry identifier | DFDA-VIT-D-001 | |

| Combined | Evidence Grade | Validation status | Validated/Promising/Signal |

| Causal Confidence | Probability of true effect | 0-1 scale |

Evidence grades:

- Validated: Confirmed by pragmatic RCT (p < 0.05, consistent direction)

- Promising: High PIS (>0.6), awaiting or in trial

- Signal: Moderate PIS (0.3-0.6), hypothesis only

15 Limitations and How They’re Addressed

The two-stage design addresses the fundamental limitations of purely observational pharmacovigilance while acknowledging residual constraints.

15.1 Fundamental Limitations: Observational Stage

These limitations apply to Stage 1 (observational analysis) but are addressed by Stage 2 (pragmatic trials):

| Limitation | Stage 1 Status | Stage 2 Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Cannot prove causation | Hypothesis only | Randomization establishes causation |

| Cannot replace RCTs | Generates candidates | Pragmatic trials ARE simplified RCTs |

| Cannot handle strong confounding | Confounding by indication | Randomization eliminates confounding |

| Cannot generalize beyond population | Self-selected trackers | Pragmatic trials use real-world populations |

15.2 Methodological Weaknesses: Addressed by Two-Stage Design

| Weakness | Stage 1 Impact | Two-Stage Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Arbitrary baseline definition | Acceptable for signal ranking | Trial uses randomized comparison, no baseline needed |

| Hyperparameter overfitting | May inflate some correlations | Trial confirms true effect, calibrates models |

| Self-selection bias | Non-representative sample | Pragmatic trials embed in routine care |

| Measurement error | Self-report limitations | Trials can use objective endpoints |

| Hawthorne effect | Tracking changes behavior | Trials embedded in normal care minimize this |

| Multiple testing | Millions of comparisons | Only top signals proceed to trial (TPS filter) |

| Temporal confounding | Seasonal/life event effects | Randomization eliminates systematic bias |

| Confounding by indication | Sicker patients take more treatment | Randomization balances severity |

15.3 Residual Limitations

Even with the two-stage design, certain limitations remain:

- Resource constraints: Cannot trial all promising signals; prioritization required

- External validity: Pragmatic trial populations still may not represent all subgroups

- Rare outcomes: Very rare adverse events may require larger observational signals

- Behavioral interventions: Some treatments (diet, exercise) difficult to blind

- Long-term effects: Pragmatic trials typically 6-12 months; decades-long effects require observational follow-up

- Interaction effects: Two-way drug interactions testable; higher-order interactions remain observational

15.4 What This Framework CAN Now Do

With pragmatic trial integration, the complete framework can:

- Establish causation: For high-priority signals, randomization proves causal relationships

- Generate validated outcome labels: Quantitative effect sizes with experimental backing

- Scale discovery: Analyze millions of pairs observationally, confirm thousands experimentally

- Continuous validation: Learning loop improves both observational and experimental components

- Enable precision medicine: Subgroup analyses identify responders vs. non-responders

- Inform regulatory decisions: Validated labels provide evidence for treatment recommendations

- Reduce research waste: Focus expensive trials on signals most likely to confirm

16 Implementation Guide

16.1 System Architecture

The framework consists of five sequential processing layers:

- Data Ingestion Layer: Collects measurements from wearables, health apps, EHR/FHIR systems, manual entry, and environmental sensors

- Measurement Normalization: Standardizes units, timestamps, deduplicates records, and attributes data provenance

- Variable Ontology: Assigns semantic categories, default temporal parameters (\(\delta\), \(\tau\)), and filling value logic

- Relationship Analysis Engine: Generates predictor-outcome pairs, performs temporal alignment, computes correlations, and optimizes hyperparameters

- Population Aggregation: Combines individual N-of-1 analyses, computes confidence intervals, detects heterogeneity and subgroups

- Report Generation: Produces outcome labels, treatment rankings, and safety/efficacy signals

Complete implementation details, database schemas, and reference code are available in the supplementary materials repository.

16.2 Core Algorithm: Pair Generation

Algorithm 1 (Temporal Pair Generation): Given predictor measurements \(P = \{(t_j^P, p_j)\}\) and outcome measurements \(O = \{(t_k^O, o_k)\}\), onset delay \(\delta\), duration of action \(\tau\), and optional filling value \(f\):

Case 1 (Predictor has filling value): For each outcome measurement \((t_k^O, o_k)\): \[p_k = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{|W_k|}\sum_{j \in W_k} p_j & \text{if } W_k \neq \emptyset \\ f & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\] where \(W_k = \{j : t_k^O - \delta - \tau < t_j^P \leq t_k^O - \delta\}\). Output pair \((p_k, o_k)\).

Case 2 (No filling value): For each predictor measurement \((t_j^P, p_j)\): \[o_j = \frac{1}{|W_j|}\sum_{k \in W_j} o_k\] where \(W_j = \{k : t_j^P + \delta \leq t_k^O < t_j^P + \delta + \tau\}\). Output pair \((p_j, o_j)\) only if \(W_j \neq \emptyset\).

16.3 Core Algorithm: Baseline Separation

Algorithm 2 (Baseline/Follow-up Partition): Given aligned pairs \(\{(p_i, o_i)\}_{i=1}^n\):

- Compute predictor mean: \(\bar{p} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n p_i\)

- Partition into baseline \(B = \{(p_i, o_i) : p_i < \bar{p}\}\) and follow-up \(F = \{(p_i, o_i) : p_i \geq \bar{p}\}\)

- Compute outcome means: \(\mu_B = \mathbb{E}[o \mid (p,o) \in B]\) and \(\mu_F = \mathbb{E}[o \mid (p,o) \in F]\)

- Return percent change: \(\Delta = \frac{\mu_F - \mu_B}{\mu_B} \times 100\)

16.4 Core Algorithm: Predictor Impact Score

def calculate_user_pis(correlation, statistical_significance, z_score,

interest_factor, aggregate_pis):

"""

Calculate user-level PIS for individual N-of-1 analysis.

PIS_user = |r| × S × φ_z × φ_temporal × f_interest + PIS_agg

"""

Z_REF = 2 # Reference z-score (significance threshold)

# Strength: absolute correlation

r = abs(correlation.forward_pearson)

# Effect magnitude: normalized z-score factor

phi_z = abs(z_score) / (abs(z_score) + Z_REF) if z_score else 0.5

# Temporality: forward vs reverse correlation ratio

r_fwd = abs(correlation.forward_pearson)

r_rev = abs(correlation.reverse_pearson)

phi_temporal = r_fwd / (r_fwd + r_rev) if (r_fwd + r_rev) > 0 else 0.5

# Composite user-level score

radar = r * statistical_significance * phi_z * phi_temporal * interest_factor

radar += aggregate_pis

return round(radar, 4)

def calculate_aggregate_pis(correlation, n_users, n_pairs,

high_outcome_change, low_outcome_change,

weighted_avg_vote, gradient_coefficient):

"""

Calculate population-level aggregate PIS.

PIS_agg = |r_forward| × w × φ_users × φ_pairs × φ_change × φ_gradient

"""

SIGNIFICANT_USERS = 10

SIGNIFICANT_PAIRS = 100

SIGNIFICANT_CHANGE_SPREAD = 10

# Strength: absolute forward correlation

r_forward = abs(correlation.forward_pearson)

# Consistency: user saturation

user_saturation = 1 - exp(-n_users / SIGNIFICANT_USERS)

# Consistency: pair saturation

pair_saturation = 1 - exp(-n_pairs / SIGNIFICANT_PAIRS)

# Clinical significance: change spread saturation

change_spread = abs(high_outcome_change - low_outcome_change)

if change_spread == 0:

change_spread = 1 # Prevent zero PIS

change_saturation = 1 - exp(-change_spread / SIGNIFICANT_CHANGE_SPREAD)

# Biological gradient: dose-response

gradient_factor = min(gradient_coefficient, 1.0) # Cap at 1.0

# Composite aggregate score

radar = (r_forward * weighted_avg_vote * user_saturation *

pair_saturation * change_saturation * gradient_factor)

return round(radar, 4)

def calculate_z_score(outcome_percent_change, baseline_rsd):

"""

Calculate z-score: effect magnitude normalized by baseline variability.

z = |Δ%| / RSD_baseline

z > 2 indicates p < 0.05 (statistically significant)

"""

if baseline_rsd and baseline_rsd > 0:

return round(abs(outcome_percent_change) / baseline_rsd, 2)

return None

def calculate_temporality_factor(forward_correlation, reverse_correlation):

"""

Calculate temporality factor: evidence for forward causation.

φ_temporal = |r_forward| / (|r_forward| + |r_reverse|)

Returns 0.5 if ambiguous, approaches 1 if forward dominates.

"""

r_fwd = abs(forward_correlation)

r_rev = abs(reverse_correlation)

if r_fwd + r_rev == 0:

return 0.5 # No evidence either way

return round(r_fwd / (r_fwd + r_rev), 4)

def calculate_percent_change_from_baseline(baseline_mean, followup_mean,

is_percent_unit=False):

"""

Calculate percent change from baseline.

Δ% = ((followup - baseline) / baseline) × 100

"""

if baseline_mean == 0 or is_percent_unit:

return round(followup_mean - baseline_mean, 1)

return round((followup_mean - baseline_mean) / baseline_mean * 100, 1)

def calculate_interest_factor(predictor_var, outcome_var):

"""

Calculate interest factor penalizing spurious variable pairs.

f_interest = f_predictor × f_outcome × f_pair

"""

factor = 1.0

# Predictor-specific penalties

if predictor_var.is_test_variable():

factor /= 2

if predictor_var.is_app_or_website():

factor /= 2

if predictor_var.is_address():

factor /= 2

# Outcome-specific penalties

if outcome_var.is_test_variable():

factor /= 2

if not outcome_var.is_outcome():

factor /= 2

# Pair appropriateness

if not predictor_var.is_predictor():

factor /= 2

if is_illogical_category_pair(predictor_var, outcome_var):

factor /= 10

return factor16.5 Database Schema (Key Tables)

-- Variables (predictors, outcomes, etc.)

CREATE TABLE variables (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(255),

variable_category_id INT,

default_unit_id INT,

filling_value FLOAT,

filling_type ENUM('zero', 'value', 'none', 'interpolation'),

onset_delay INT, -- seconds, default delay before effect

duration_of_action INT, -- seconds, how long effect persists

outcome BOOLEAN, -- is this an outcome variable?

predictor_only BOOLEAN, -- can only be a predictor (e.g., weather)

valence ENUM('positive', 'negative', 'neutral'), -- interpretation of higher values

is_goal BOOLEAN, -- something users want to optimize

controllable BOOLEAN, -- user can directly modify

boring BOOLEAN, -- filter flag for uninteresting variables

predictor BOOLEAN, -- can influence outcomes

optimal_value_message VARCHAR(500), -- pre-computed recommendation text

best_predictor_variable_id INT, -- strongest predictor for this outcome

best_outcome_variable_id INT -- most affected outcome by this predictor

);

-- Measurements

CREATE TABLE measurements (

id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

user_id BIGINT,

variable_id INT,

value FLOAT,

unit_id INT,

start_time TIMESTAMP,